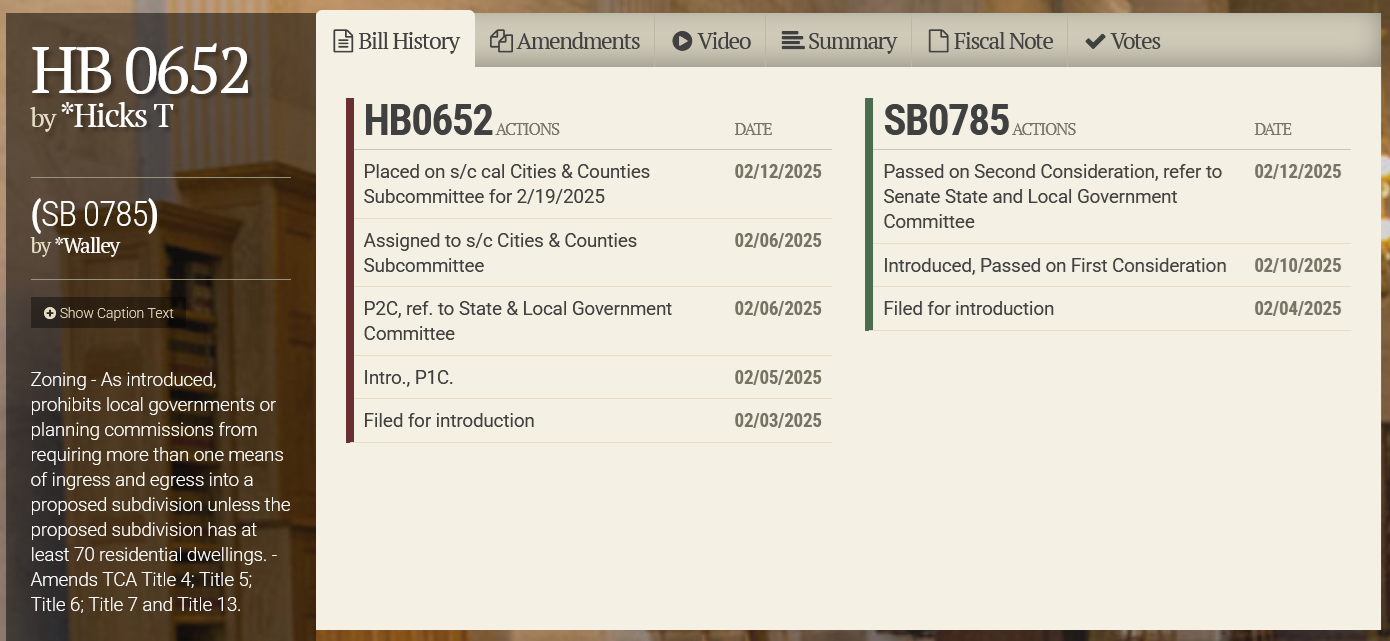

A bill in the Tennessee state legislature seeks to micro-manage subdivision design at the state level and take it away from local bodies. HB652 SB785 prohibits local governments or planning commissions from requiring more than one means of ingress and egress into a proposed subdivision unless the proposed subdivision has at least 70 residential dwellings.

The Knox Community Planning Alliance opposes HB652 SB785 as introduced. This bill is not solving a problem for the community. The bill creates a state-level mandate and takes control away from the local officials, who are in the best position to look at a particular development and determine the layout and requirements. Only when we have local elected officials armed with the authority and tools necessary to make good decisions can the electorate hold accountable these officials for the decisions made.

The Town of Farragut, Knoxville and Knox County all have requirements that new subdivisions provide for future street connections to adjoining property. It is unclear what this bill would do for that requirement – creating stub-outs to adjacent property. KCPA documented the poor results when the requirement isn’t enforced and we only have 1 entrance for neighborhoods – where 2 houses share a fence line but are 2.5 miles away on the public streets.

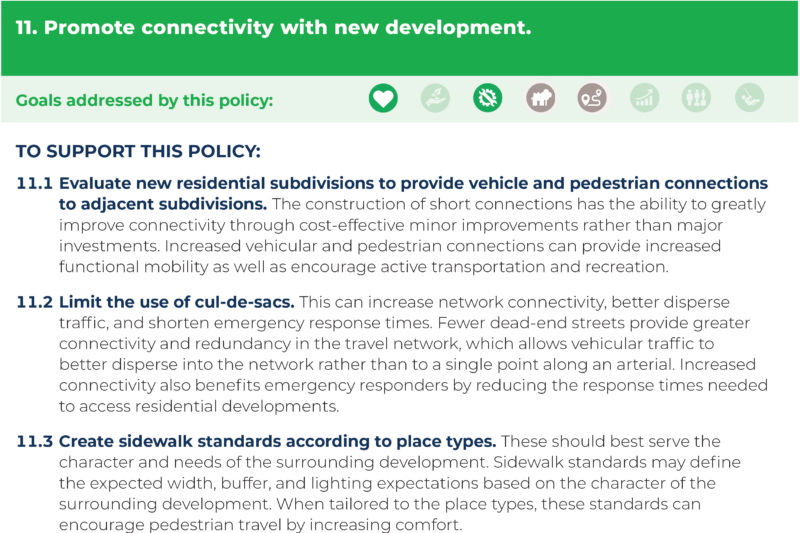

For Knox County, this bill would interfere with implementing Policy 11 in our recently adopted Comprehensive Land Use Plan. Policy 11 (below) is “Promote connectivity with new development.” It has actions to 1) Evaluate new residential subdivisions to provide vehicle and pedestrian connections to adjacent subdivisions, 2) Limit the use of cul-de-sacs, and 3) create sidewalk standards according to placetypes.

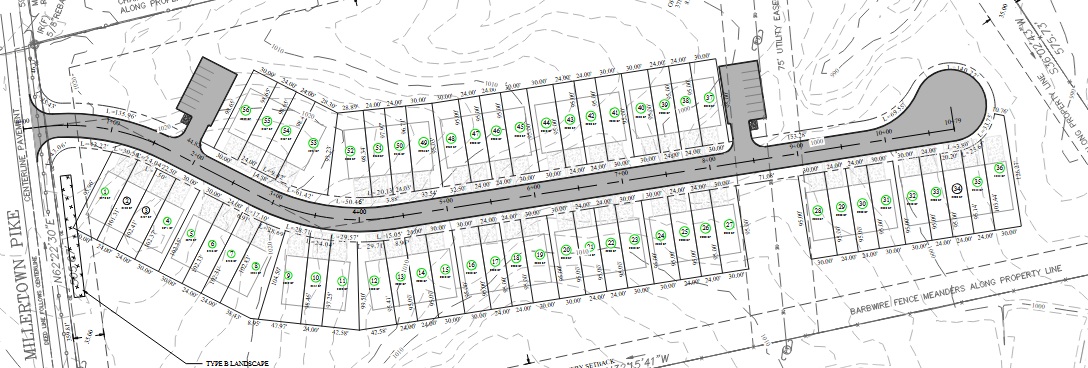

Limiting a subdivision to one and only one ingress / egress point often results in a this type of a layout – the “thermometer bulb” subdivision design – a long street, perfect for speeding, and a cul-de-sac at the end.

Cul-de-sacs have pros-and-cons. Often the lots on cul-de-sacs have less traffic, usually are larger lots, offer more privacy, and bring more income to a land developer.

But cul-de-sacs and neighborhoods with only a single ingress / egress point have streets and infrastructure that exist for one and only one purpose: to provide access to the homes built around it.

The math for cul-de-sac design doesn’t add up at all, as this article from a planner in Gallatin, Tennessee analyzes. Cul-de-sac neighborhoods are not self-sustaining; they cost more money to maintain than they contribute in tax revenue. They must follow International Fire Code regulations. Dead-end streets that are longer than 150 feet must include enough space for fire trucks to properly turn around, which means that a roundabout should have a 96-foot diameter. If dead-end streets are longer than 500 feet, they must also be 26 feet wide. The standard width of streets is 20 feet, which means that lengthy dead-end streets are more must be wider than they could if they were a grid system. Wider streets and 96-foot diameter cul-de-sacs require more asphalt, and more land, which make them more expensive to build and maintain.

If a subdivision developer wants the benefits of cul-de-sacs and limited entrances, they can pay for it by creating private streets and have the residents pay for the maintenance of those streets. If the developer wants the public to take on the cost of maintaining those streets, then developers need to make them useful to the public-at-large, not just the homeowners on that street.

Having only a single entrance / exit for residents exacerbates congestion and reduces mobility. Traffic is channeled onto overcrowded streets outside the subdivision. Everybody is forced to take longer trips. Safety is reduced – vehicles that could travel internally between subdivisions are instead forced to turn onto higher-speed connecting streets. Think of your child’s school bus. If you have two adjacent subdivisions that aren’t connected, the school bus must come down your street, turn around at a cul-de-sac, exit your subdivision by making a turn onto a busier road (usually at peak traffic times), and then travel down that busy road a bit to get to the next subdivision. This results in more turning movements. Each turning movement has a slight risk of accident or injury. Add in all of the delivery trucks and other traffic a day, and the result is adding traffic onto already busy main roads.

We think an excerpt from this article sums it up perfectly:

Whenever a new subdivision is built, private developers determine the layout of the neighborhood. They draw up the lots and blocks, and build the streets, utilities, and houses in accordance with the subdivision regulations and other applicable codes. Once complete, they sell the houses, convey ownership of the streets to the city and walk away.

Their goal is simple: to maximize profits, while meeting the minimum standards of the applicable regulations. They don’t have to worry about the long-term needs of an evolving city, or the flexibility or connectivity of a transportation system.

But we do. Because when the developer walks away, that street network becomes ours. If we don’t like it, we can’t re-gift it. We can’t donate it to Goodwill. We’re stuck with what they’ve built. And when neighborhoods are designed solely for cars, it doesn’t matter how many bike lanes and transit stops we build, because people are going to drive.